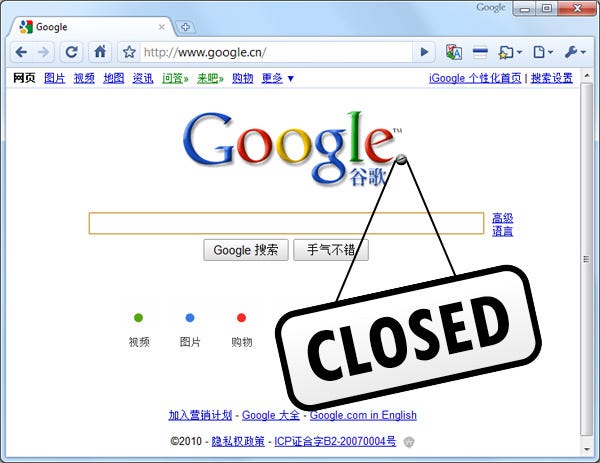

With Google exiting china we can hardly hide our glee. It seems the tiger may finally steal a march over the dragon. Pop nationalistic sentiment may rise in some newspaper columns and talk shows calling it a victory of models of government. The model’s of government debate which is intertwined with foreign investment is not new. Prime Minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh has been quoted in a CNN interview as stating that, “[b]ecause India adopts democratic system, India develops not that rapidly as China does.” For me this is a wider issue which cannot be settled with reference to the exit of Google from China.

For me, a more relevant, immediate and natural factor which comes out are the limits and allowances of private autonomy afforded to foreign investors to run a business especially in high technology industries. Online businesses are special, they are not your ordinary brick and mortar stores, by their very nature they are global and the subjection of a national regime which is unique is counterintuitive for them. When that national legal order, demands high compliance costs, change in technological and business models, the online service will just shift, rather than stay. Here it may seem cynical, but the determinant for economic domicile seems to be a balance between the quantifiable costs against the potential gains.

As a country we do not have to gloat at Google’s exit from China. As a country which is continuously threatened by terrorism, we routinely have calls for strengthening legal provisions. Here potential technological misuse is used as rationale for imposing burdens on online service and technological providers. These are same compliance costs which made Google leave China. This is more than mere apprehension and was visible recently when the government concerned about the encryption in Blackberry devices sought the universal decryption key for all messages and devices on Blackberry.

India is also in several respects a country where a thin level of protection is afforded to online service providers. The amended Section 79 of the Information Technology Act does improve upon the level of protection (by way of exception from liability) which is provided to online service providers however they can still be subjected to a long and arduous trial (there is no bar to suits against them, only exception from liability). Moreover, the section relies on antiquated statutory language, where it says, the information should not be, “selected” or “initiated” for communication by the intermediary. Most social media services, aggregate data and present information and it is debatable when such cases come to trial as to what protection will be afforded to intermediaries. What I sense is that such legal provisions will due to their ambiguity promote some level of self-censorship to avoid any legal action.

The exit of Google for China should lead us to an examination to our internet policy and what forms of costs are being leveled on online service providers by our legal system. In my opinion, it is better than badgering Google’s India staff with questions of the, “what this means for India” variety. A start is posing the same question to ourselves.

Related articles

- Report: China leaders ordered Google hacking (abclocal.go.com)

- Key Chinese official targeted Google: WikiLeaks (cbc.ca)

- No, Google Won’t Share Gmail’s Encryption Keys With Indian Government (techie-buzz.com)