Absent a pragmatic partnership the Supreme Court decision on the powers of the State Government and the LG in Delhi is only likely to lead to future rounds of litigation

On the ground floor of the Tis Hazari Complex a special class of courts have the jurisdiction to adjudicate on cases on matrimonial and guardianship. Popularly referred to as, “family courts”, they are found in court complexes around Delhi where legal arguments mesh with high emotion, heartbreak but also reconciliation and compromise.

Over the past four years, a charged political environment has lead to the loco parentis of Delhi, the Lieutenant-Governor (LG) and the State Government to fight an acrimonious battle over its control. Each claimed overlapping exclusivity of jurisdiction and power through a series of notifications which generated a constitutional gridlock. With the Supreme Court pronouncing judgement on these disputes, and with both parties claiming victory, questions and confusion continues to arise.

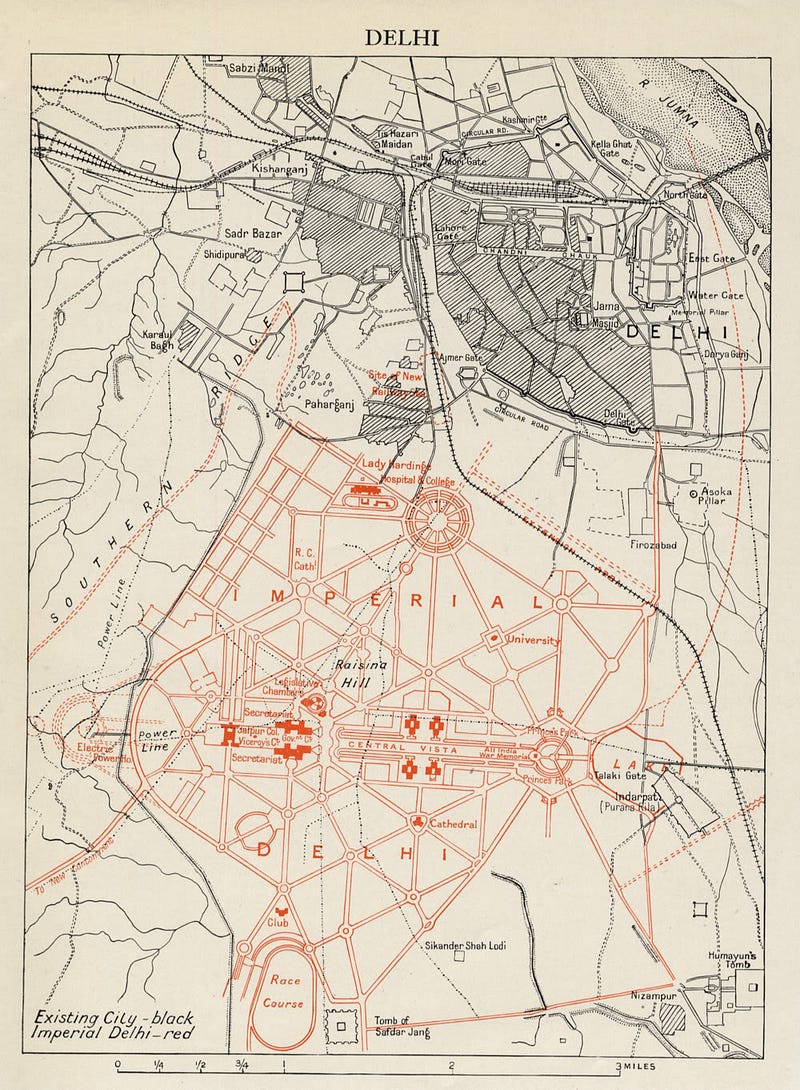

To understand the Supreme Court judgement one first has to understand the creature that is Delhi. It is the seat of the Central Government and from the adoption of the Constitution was directly administered by it without a state assembly. This was to ensure the smooth functioning of a seat of power from the interference by a direct electorate which would prefer its own interests over rest of the country. But people continued to fall in love with Delhi, calling it their home. It continued to grow as a metropolis on its path to becoming one of the most populous cities of the world advocating the need for a local government. Such practical realities caused demands for statehood which were satisfied by an uneasy compromise of the Constitution (Sixty-ninth Amendment) Act, 1991 which inserted Article 239AA in the Constitution of India and the enactment of the Government of National Capital of Delhi Act, 1991 with the Transaction of Business Rules, 1993.

These legal texts form the basis of the determination of the executive and legislative competence of the Delhi Government, but they only created a tenuous relationship which lacked clear definition due to a mismatch in expectations between the residents of Delhi who now voted for a local government, but which had little power without the concurrence of the LG who was effectively under the control of the Union Government. When the relationship between the LG and the present State Government lead by Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal broke down, characterized by a lack of trust and political brinkmanship the welfare and development of Delhi stalled.

At the root of this was the interpretation of Article 239AA which was a not happily worded. While a more textual, conservative interpretation reserved greater power for the LG far beyond the reserved subjects, “police”, “land” and “public order” which remained under complete and exclusive central control. At play was a portion of this provision that stated two things. First the LG would act on the aid and advice of the Council of Ministers of the State Assembly. But more importantly the second, that in instances of disputes between the LG and the Council of Ministers on any matter, the President of India would be the arbiter. As the President in turn acted on the aid and advice of the Union Government, it presented a situation where the State Assembly would be reduced to a nominal and titular body.

The Supreme Court by its judgement, rejects such reading preferring a purposive interpretation which carries forth the constitutional values of democratic control. It reasons that the people of Delhi deserve to have a say on how the city functions through its State Assembly, and the Central Government cannot completely usurp its functions acting through the LG. Such a proxy administration on day to day matters cannot be the norm and the LG would have to defer to the Delhi Government, resorting to references to the President only in exceptional cases.

But there remains reason to worry for two reasons. The first is that the while expounding this judgement in excessive verbiage the Supreme Court has omitted sufficient clarity on the criteria and instances of such, “exceptional cases” where the power of the LG for reference continues to exist. Second, this judgement is only concerned the high principles of constitutionality, but not the practical application which will be determined subsequently. This will lead to many further rounds of litigation in which both the LG and the Delhi Government will try to manoeuvre the instant decision to specific notifications on which both will seek primacy.

Litigation is a process that requires time, drains litigants, and often spurs further conflict. Such a cynical outcome driven by electoral politics may cause this judgement, which privileges democracy over central power to become a pyrrhic victory. Here rests an important lesson — — in a war of the roses it is the children who ultimately loose. Today the children of this strange and beautiful capital look beyond the courts to our elected representatives and its politicians for governance.

For all her critics and faults, its former Chief Minister Shiela Dixit states a sound axiom in her autobiography, “the tussle between governance and politics was ongoing and I could never hope for an ideal scenario. What I needed to do was to remain focussed and walk towards the future in step with the needs and aspirations of the Delhiite. I too was a Delhiite after all.”

(An edited version of this article was first published in the Hindustan Times on July 7, 2018)