The answer is obvious and the reasons are historic. Let us step back into time to and then quickly pace to the notification last week authorising government agencies to intercept, monitor and decrypt digital information.

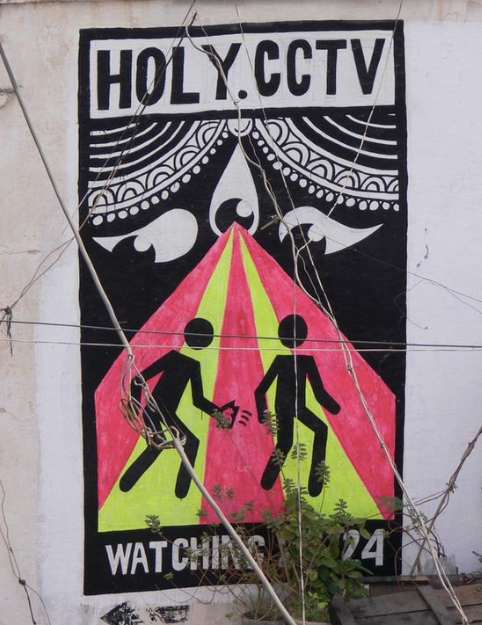

So has the government merely issued a routine notification empowering intelligence agencies to gather intelligence to prevent terrorism or is this the creation of a surveillance state? While the answer is fairly obvious, it will be better understood with analysis that is divided into three parts.

The first documents the history of interception given the narrative that, “no new powers have been conferred” by the recent Ministry of Home Affairs order. The second marks how surveillance works at present and the incumbent problems. In conclusion, this piece examines the government response and prompts a thought on the needed solution. To properly understand the Ministry of Home Affairs order, one has to step back in time to look at the riveting history of surveillance reform that emerges from tales of political intrigue.

How it all started

Due to the fractious politics of the early 1990s, politician and former prime minister Chandra Shekhar accused the VP Singh government of illegal phone tapping of opponents. These disclosures led to India’s pre-eminent human rights organisation the People’s Union for Civil Liberties approaching the Supreme Court. It was discovered that no procedure or even proper safeguards existed for telephone tapping.

The court laid down certain guidelines in its decision in 1996. During arguments, there was a specific suggestion for judicial oversight, which was rejected. These guidelines became an important marker that must be examined in the context of that time — keeping in mind the prevalent technology, then a fixed-line telephone, and the volume, nature and extent of personal information. The court’s guidelines were later formally placed in the Telegraph Rules with the insertion of Rule 419-A. This became the operative structure for telephone tapping.

A systemic rot sets in

Over the years, these guidelines have proved to be ineffective. Phone tapping scandals continued to arise, pointing to design faults — ranging from the lack of independent oversight of interceptions to agencies which were not under any parliamentary supervision or control. Incidents, such as allegations made by Amar Singh or the Radia Tapes, evidenced a systemic rot but they were limited to political personalities, or sometimes industrial espionage, and the popular argument for surveillance reform lacked a broader constituency. There were also counter arguments of state security and anti-terrorism measures made in support of surveillance.

Repeated calls for reform have been made over the years. The Justice AP Shah Committee on Privacy included recommendations on this issue and the Department of Personnel and Training even commenced an exercise to draft a comprehensive Privacy Act which (as per leaked versions) included such reforms. However, to date, there have been hardly any meaningful changes in India’s government surveillance framework to check abuse and to protect individual rights.

As per India’s telecom regulator, about four in ten Indians today has a smartphone. These devices are a passport to the digital world that is making our lives better via pervasive data gathering. This knowledge exchange is not only conducted by large global online platforms but also government services. The amount of personal information available on handheld devices today is unhindered by technical capability or even economic cost as data storage and acquisition costs continue to drop. Economically and socially, personal data is not the new ‘oil’ as many have put it, it is power over the way people think, act and function.

New rules perpetuate old abuse

The rules for digital surveillance were made in 2009 by the Central Government and included a specific power under Section 69 of the Information Technology Act.

Though this power had existed since 2000, when parliament first legislated the IT Act, its scope was expanded by an amendment in 2008. These changes and the 2009 rules focused on data acquisition from large online platforms which serve as digital honeypots for governments. The rules are closely modelled on the telephone tapping framework and follow a similar model — but they extend it further in terms of power.

For instance, they permit surveillance in terms of monitoring data traffic of an individual or class of persons or relating to any subject and via more than one computer resource. The IT rules claim constitutionality in the Supreme Court decision in the 1997 telephone tapping case, which did consider an expanded spectrum of personal data acquisition.

There are deviations but in contrast with the telephone tapping and the digital snooping rules, it is a clear inference that the scope of power and acquisition of personal information is deeper, wider and pervasive. Digital snooping pierces the skull into the depths of human emotion, it cuts to the bone to the mildest kinesis of physical action.

Meanwhile, the safeguards are extremely deficient and bear the same design flaws of the telephone tapping architecture. The agencies who should be tasked with surveillance have still not been created by parliamentary enactments, there is a concentration of power in the executive branch and illegally gathered data is admissible as evidence in court cases as there is no necessity for judicial warrants. Little or no safeguards exist as recommended most notably by the Justice AP Shah Committee report on privacy.

A weak defence by the Government

On Friday, when a political maelstrom broke out, the Minister for Finance and Corporate Affairs made a spirited defence which deserves some examination to understand the path ahead. Elements of this defence were contained in the parliamentary reply, a blog post, and a clarification issued through a press statement by the Ministry of Home Affairs. Let’s look at it threadbare from the point of legality and accuracy rather than apportioning blame to political parties.

The first point is that the notification, that authorises 10 central agencies to intercept, monitor and decrypt all data contained in any computer, is only a continuation of past practice. It is routine and has been followed even prior to 2009. This omits to consider that the earlier powers and requisition of personal information for telephone tapping were limited as compared to the expanse of digital snooping. It also does not consider that the notification, a fresh one, in fact, activates 2009 rules — as no earlier such notification existed to empower intelligence agencies. What was pre-existing were notifications for telephone tapping under Rule 419-A of the Telegraph Rules. This is a new development even if the context for it was created years ago.

The second point — that the notification is necessary for protecting individual rights, as, without it, police officers were acting beyond the purview of law. It bears repetition, that, if they were, any such action was unconstitutional. Without authority, such interception, monitoring and decryption could not be carried out itself. Hence when viewed holistically the MHA notification activates broad powers in favour of ten central agencies to send requisitions to the Ministry of Home Affairs. It ultimately is a fresh development which tremendously expands their powers from tapping telephones to fine grains of our digital data.

The third justification was that this notification was necessary for intelligence agencies to prevent acts of terrorism. There is little quarrel here with the objective. Terrorism hurts people and we need to secure our country. What is in dispute is the proportionality of the legal power to achieve these objectives. Only in August 2017, nine judges of the Supreme Court laid down an authoritative judgment on the right to privacy whose majority opinion stresses on heightened safeguards for individuals and tougher scrutiny for officials. Even the majority Aadhaar decision, which came as a disappointment for many activists, recognises the role of judicial warrants which require a judge’s signature. This is in recognition that the telephone tapping safeguards may be proper in 1996 as per the court. However, times have changed. Legal doctrine has evolved to recognise that a smartphone requires a smarter approach and safeguards to surveillance.

Hence, rather than reviewing the 2009 rules, the government activated them. This was not a continuation of a past practice, but a fresh one which expanded previous abuse. Even if the notification is just a continuation of past practice, it has perpetuated a broken system prone to abuse.

The government’s approach is not surprising, given that the Ministry of Electronics and IT is considering the Justice BN Srikrishna drafted Draft Data Protection Bill that does not pose any legal intervention on surveillance. A separate report authored by them disingenuously hides behind incoherent arguments and legal doctrine in marking this task to a separate initiative, ignoring the practical reality of the threat to privacy arising both from the private and the public spheres of data gathering.

What is the fix?

It is a comprehensive privacy law such as the Indian Privacy Code. The MHA notification is only one in a range of government programs, many which we do not fully know about, that are building surveillance capabilities. These will no longer target those who wield or aspire for power, but more ordinary people, minorities and the poor who lack resources to safeguard themselves. As concerned citizens, while there may be many versions of the specific minutiae of legality, it should be our common claim that data protection is incomplete without surveillance reform. Without, it India will become a surveillance state.

A version of this explainer was published by Bloomberg Quint on December 23, 2018.