About two decades ago, in a one page op-ed, Clyde Wayne wrote, “Warfare on the digital commons invites more regulation and adds to a deteriorating and antiquated Internet. Splintering, though it will be criticized as Balkanization, increases our options and wealth.” Though inadequately reasoned, “balkanisation” became a popular import in tech policy debates, with commentators voicing anxieties around censorship and surveillance. These fears have surfaced in policy debates over the Russian invasion of Ukraine. So, is the Internet really breaking up as a global network?

On February 24, 2022, Russian president Vladimir Putin announced a “special military operation” in a televised address. Coinciding with this, there was a spike in cyberattacks first against Ukraine, and then against Russia. There were competing narratives about the invasion on social media, ranging from calls for humanitarian aid to online disinformation. In addition to this, there has been increased social media censorship in Russia, which first made demands of Big Tech, and then eventually blocked Facebook and Twitter.

These blockings hold context that is important to examine. An underlying resentment is captured in assertions by Russian state officials that social media platforms are primarily “American Internet companies” that fail to comply with national interests and legal frameworks in Russia. Just before the blocking, the platforms were (and continue to be) overwhelmingly critical of the invasion and further restricted disinformation alleged by preventing monetisation, or availability of Russian media to comply with EU sanctions.

They are perceived as partisan in their enforcement and response to legal requests. This has not helped with the exit of global tech companies, and more recent sanctions directing search engines (primarily Google) to delist Russian content.

A utopian dream?

Increased censorship and exit of these platforms prevent Russians from participating in global communications, leading many to question whether these events accelerate or establish a “splintering” of the global Internet.

Does a global Internet with information freely flowing beyond national borders really exist? This is an idealised vision based on an incorrect technical understanding and a presumption of shared values. Shira Ovide of The New York Times provocatively says the “global Internet is a mirage” primarily dominated by American companies (with the exception of China).

A more nuanced explanation is offered by Internet governance experts who state that, “the Internet is neither fragmented nor unified, it is unifragged, which means that millions of networks and services speak the same language but can freely block external users or other systems as they please… the big difference now is that the invasion of Ukraine has catalyzed collective action in this distributed system, fostering a coordinated response reflecting geopolitical divisions…”.

The Internet is experienced uniquely by people in different countries. However, at present, there is a risk in deepening divisions both in scale and scope. Current events also pose a geopolitical challenge to Russian state interests, which will lead many to wonder what the implications are for India.

What if one day, India acting in its national interest is determined to be a hostile country? Or suffers sanctions? While India is not Russia, and this may be an edge case, let us entertain this thought for a moment.

Given a tendency to be pulled in by our political biases on the invasion, or mischaracterise and overstate the problem statement, it is important to consider the institutional response of ICANN, the multi-stakeholder body tasked with taking care of the Internet infrastructure of domain names. But since it was initially backed and located in the United States, it has somewhat of a legitimacy problem despite its practiced independence. In the present conflict, it has refused a request by Ukraine to “target Russia’s access to the Internet”, noting that, “we maintain neutrality and act in support of the global Internet”.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation welcomed this move stating, “In moments of crisis, we are often tempted to take previously unthinkable steps. We should resist that temptation here, and take proposals like these off the table altogether”.

This should inspire greater confidence that the Internet remains insulated against geopolitical risks. Even in these extraordinary times, a country will not be disconnected from the Internet.

The India question

However, what is the possibility of large social media platforms exiting India, or being completely blocked? While I am far from an expert on diplomacy, such outcomes seem unlikely.

India offers lower revenue per user for technology companies, but the market size is large (if not the largest) due to high telecom connectivity. This is particularly true for large social media companies, which gain from network effects and have commercial incentives to maintain services in countries hostile to the United States.

As the editorial board of The New York Times notes, “American corporations do little to counteract Balkanization and instead do whatever is necessary to expand their operations. If the future of the internet is a tripartite cold war, Silicon Valley wants to be making money in all three of those worlds.”

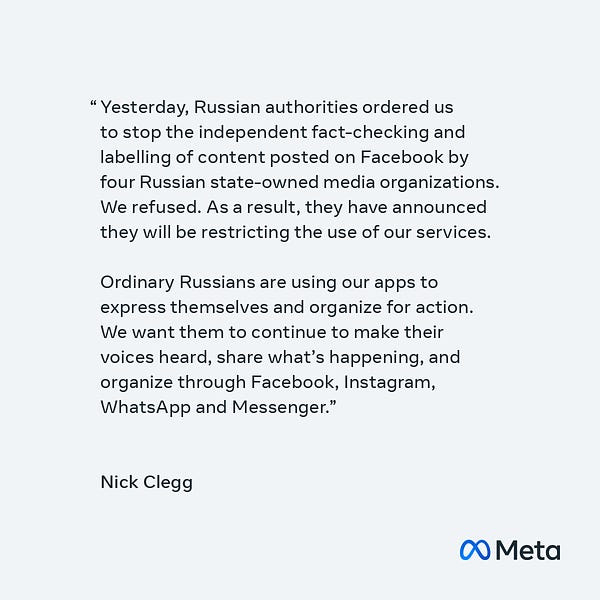

The large user base also makes it difficult for a national government to boot out platforms without inviting criticism from its nationals. It has been evident in the continued operation of YouTube (without sales) that despite censoring, RT has not yet been blocked in Russia. The second reason for the continuation of services is their corporate objective, which at its core, is to provide global connectivity services. This is best expressed through political principles of free speech and expression of end-users as voiced by Nick Clegg, President, Global Affairs at Meta, who posted on Twitter.

In India, there exists evidence for this, with many social media platforms following a negotiated path for years, in which, in compliance with local law, they fail on their global standards of transparency or free speech. This is captured in the compliance they have enforced for social media rules issued last year, with the industry body IAMAI welcoming them.

The third and final reason is past precedent, as pointed out by Rebecca Mackinnon writing in the tech policy press that, “the Obama Administration’s Treasury Department issued general licenses clarifying that companies can allow individuals from Iran and Syria to use certain free consumer-facing services.” Hence, while there is a low likelihood of disruption of social media networks, there may be market exits by technology companies and curtailing any digital financial services to comply with international sanctions.

Home truths

From where I sit, the risks to India are largely independent of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. We have pre-existing grievances that emerge from concerns around harms caused by social media companies, their arbitrary or biased content moderation practices and nationalistic resentments against foreign Silicon Valley companies clearly found in debates around data.

While many of these concerns deserve larger debate, we should be careful to extrapolate from current world events to our existing biases. At best, what may deserve wider examination is our own national response to Big Tech, particularly social media companies.

As Allie Funk and Grant Baker have pointed out, the Russian “splinternet” is contributed by censorship practices of Russia that have preceded its invasion of Ukraine. It includes the promotion of local online alternatives that are more susceptible to its political pressure.

We need to be mindful of these realities knowing fully well that India shuts down the Internet more than any other country. This was noted by Prof. Lemley in his recent lecture titled, “the Splinternet”, when he cautioned that, “India is an interesting example of a country that has traditionally had a relatively open Internet but which seems to be moving very heavily in the direction of locking it down….”

However, if it does not accompany an appreciation for the value of a common, shared network, we may not really splinter due to others, but mostly by ourselves.

The Article was originally published in The Signal on March 12, 2022